A Theology of Immigration | The New Yorker

After I was working with refugees in Lebanon and Turkey and the Iraqi disaster, Rwanda, different locations—you recognize, when all the pieces’s taken away from you, God is all you’ve gotten left. So we’d like a manner to discuss who God is and who we’re earlier than God, and I believe theology offers us a manner of doing that.

I’ve observed one thing related in debates round homelessness and immigration: the church does monumental quantities of labor on the bottom, however theological questions appear to have been pushed out of the broader public discourse.

I did my graduate work at Berkeley, so after I was in California, I can bear in mind someday I awoke and, actually, on the opposite aspect of the mattress the place I slept, outdoors the window, was a homeless particular person. And for me that started a protracted journey of making an attempt to grasp theology from the opposite aspect of the wall—not simply from the angle of a library or a room however from the streets and from the people who find themselves dwelling on the sting.

What you see within the church’s teachings referred to as the seamless garment of life runs by means of homelessness, runs by means of immigration, runs by means of the aged, runs by means of all different life points. After I spend time chatting with migrants at borders all over the world, I usually ask them, What’s it that you’d need individuals to listen to? Or for those who may preach on Sunday, what would you need individuals to know? And infrequently it’s about dignity. It’s about saying, We’re human beings right here, and also you’re treating us like we’re canines.

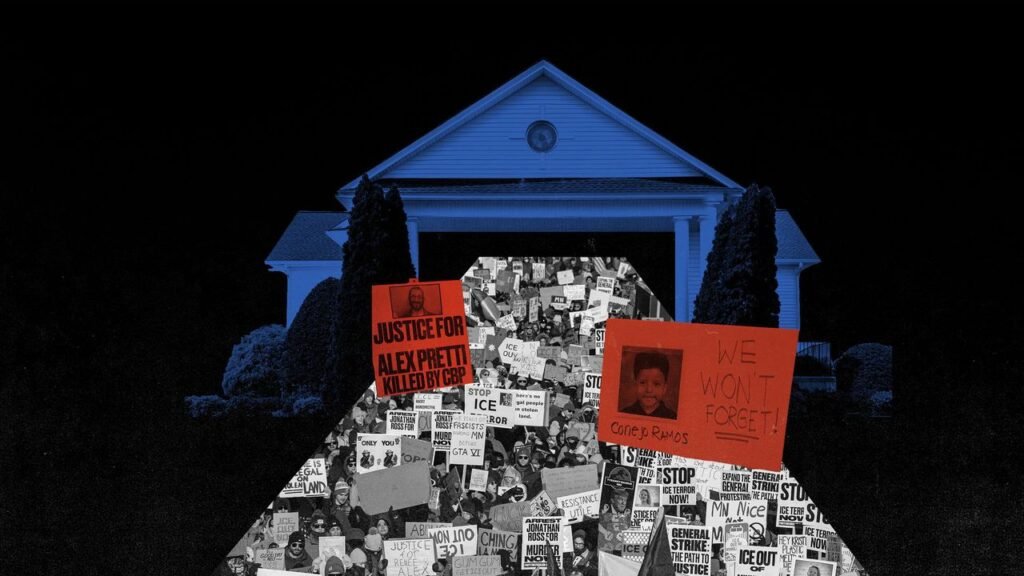

The problem is these individuals have grow to be nonpersons. I imply, they’re simply not even seen. And I believe a part of the work of the church is saying, Truly, these individuals belong in a human group, they usually belong to be seen, and due to this fact they belong within the discourse as properly.

You make this core argument that every one persons are created within the picture of God, Imago Dei. That’s one thing that many individuals would say they imagine. However while you see the information proper now, the horrific movies popping out, the responses to them—do you are feeling that concept is in disaster?

What we’ve additionally included in that understanding is that within the fall, we misplaced the likeness, however we by no means lose the picture. There’s a deep core inside us that’s indestructible—our value and our worth earlier than God.

One of many issues I usually say is that if we are able to’t see within the immigrant or within the homeless or in people who find themselves thought of completely different from us one thing of ourselves, we’ve misplaced contact with our humanity. So I believe that’s what’s at stake. We’ve deported our personal soul, if we’ve actually misplaced contact with our personal humanity.

You argue that each particular person ought to have all the pieces crucial for dwelling a very human life. What does that seem like in observe if it’s not merely open borders?

The church acknowledges that nations have the precise to regulate their borders, but it surely’s not an absolute proper. It’s subjugated to a bigger sense of what’s referred to as the common vacation spot of all items. And what does the church imply by that? In observe, that all the pieces belongs to God, and after we die, we’re gonna have to surrender all the pieces anyway. So there’s a manner during which we’re, at greatest, stewards on this life, not house owners of something in an absolute manner. And even our nationalities and our nationwide identities have solely a relative significance in gentle of a bigger imaginative and prescient of what the dominion of God is about.

The query is, what’s the narrative that shapes our consciousness on this? If the narrative is, That is my stuff, that is my nation, that is the place I belong, that is what I personal, and I’ve to defend it and shield it—that’s a method of understanding it. But when the narrative is, All the pieces I’ve is a present, and after I die, I’m going to offer all the pieces up, that I’m a steward and never an proprietor, and I may be judged by how I take advantage of what I’ve been given—that’s a special manner of inhabiting the world. If the narrative is about how can we transfer nearer to communion with God, and in nearer reference to one another, with a life and a religion that does justice, by way of caring for each other, that’s a really completely different manner of inhabiting the world.